Syngenesis is a blog dedicated to teaching artists, writers, and other world-builders how to include scientifically-grounded elements in their creations in rational and consistent ways. Co-written by our regular contributors, we explore the universe at large (and nearby!) with examples from popular fiction, fresh ideas, and realistic (or semi-realistic) alternatives to common tropes.

We also take questions—so come discover with us!

We also take questions—so come discover with us!

Futurology has a few recurring ideas that are persistently popular. The most important of these is undoubtedly the technological singularity, the notion that it is inevitable that sufficient advances in intelligence will eventually create a process of infinite growth. This idea is not easily falsified: we don't know the nature of intelligence yet, so we can't make a coherent argument, in either direction, as to whether or not infinite intelligence (or effectively infinite intelligence) is possible.

Another topic explored by futurists in recent years is the question of whether or not we are living in a simulation. This notion has broad appeal, as, if it so happens that we are in a simulated universe, it would allow us to put to rest questions about the nature of the universe by making arguments from intent, and succinctly eliminate many lines of intellectual endeavour that seek to discover the purpose and origins of life and the universe as we know it. […]

Another topic explored by futurists in recent years is the question of whether or not we are living in a simulation. This notion has broad appeal, as, if it so happens that we are in a simulated universe, it would allow us to put to rest questions about the nature of the universe by making arguments from intent, and succinctly eliminate many lines of intellectual endeavour that seek to discover the purpose and origins of life and the universe as we know it. […]

The word robot comes from a Slavic root meaning "labour." The first time the word was used, by the Czech playwright Karel Čapek, it was used to describe what is today called an android or replicant—an artificial being capable of passing for human, with genuine emotions. The idea of machines that emulate animals and humans, to various degrees of accuracy, is of course much older, and writers have traditionally revelled in finding ways of making these characters behave more artificially and more obviously as machines, from speaking monotonously to ineptitude at lying. But increasing advances in machine learning are suggesting that, perhaps, this is the wrong way of thinking, and that, instead, our fallibility and organic behaviour may actually be essential to what allows us to think.

In part two, we examined peculiar ways of creating computers, as well as past computing technologies. This part concludes the "computers in science fiction" series.

In part two, we examined peculiar ways of creating computers, as well as past computing technologies. This part concludes the "computers in science fiction" series.

Doctor Richard Daystrom, inventor of military automation, military automation testing, and the military automation testing disaster.

[…]

In part one, we looked at the nature of computers, quantum computing, and the definition of what it means for something be computable. This is all well and good for someone writing a present day or equivalent setting, but what about alien computers? How might they differ theoretically? What can be used to make them? Onward!

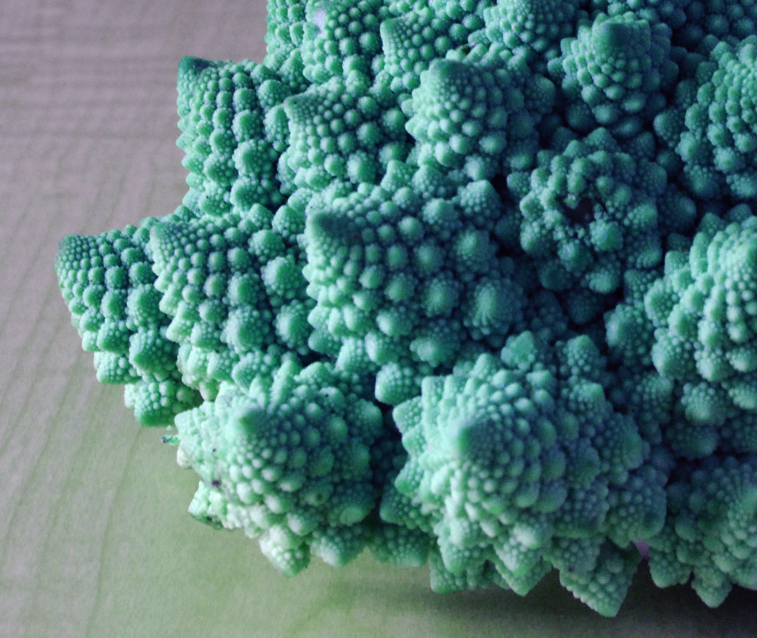

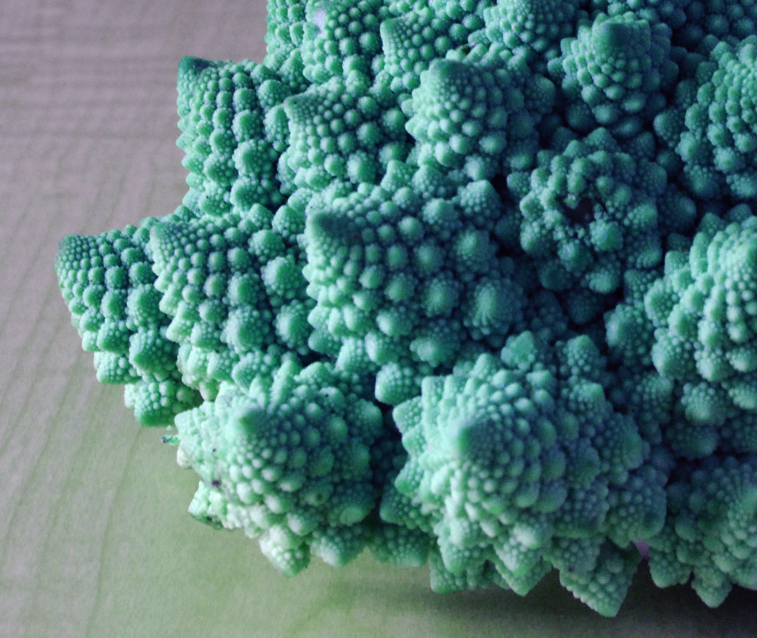

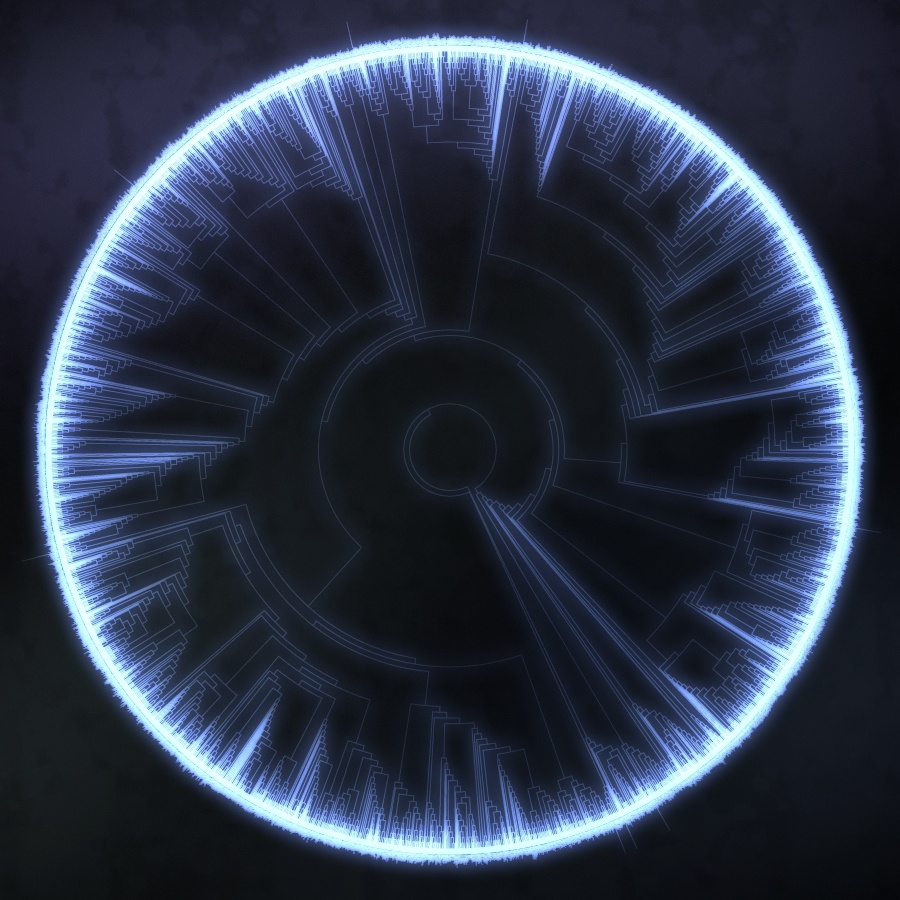

Romanesco broccoli, a naturally-occurring fractal.

[…]

In a scant century, computers utterly reshaped human civilization. They rode with us as we catapulted from the vestiges of a deeply insecure, ceremonial society, where but a few people in a few countries had the means to attain lives of intellectual fulfilment, into one that has—increasingly—become quite the opposite. Along the way, our calculating engines have inspired us to change the way we think, and the absolutism of that new wave of conceptual organization has both depressed us in its omniscience and taught us to forgive in its impartiality. Computers have given us the power to behold nature, at every level, and through that we have been humbled.

It's not surprising, then, that unique or advanced inventions—specifically computers—are prominent in so many science fiction stories.

In this three-part series, we'll look at how computers work, how alien computers might work, and how to write for convincing artificial intelligence.

It's not surprising, then, that unique or advanced inventions—specifically computers—are prominent in so many science fiction stories.

In this three-part series, we'll look at how computers work, how alien computers might work, and how to write for convincing artificial intelligence.

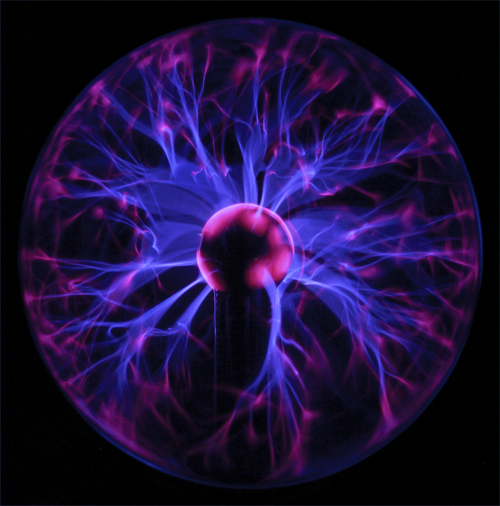

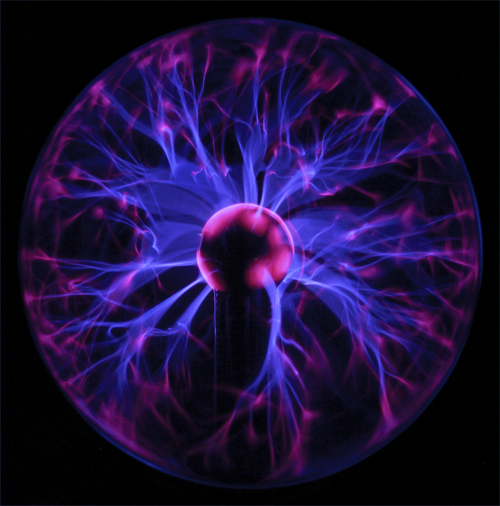

Most of them look like this.

[…]

For all our years of toil in machine learning research, we still only have one really usable model of intelligence—the mammalian brain. At first glance, it makes sense that a really complicated multicellular organism would want a control centre that can function faster than turning on and off genes or transmitting hormones, and we have examples of nervous systems (such as the one in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans) that do nothing other than steer the creature semi-randomly towards possible food sources. So how the heck did we end up with the wheel, wars, New York, and so on?

In the last part of this series, we looked at what it takes to create reproductive life, and a key real-world example of borderline living phenomena, the transposon. If you haven't read that part, now's a great time, since this part builds on it.

In the last part of this series, we looked at what it takes to create reproductive life, and a key real-world example of borderline living phenomena, the transposon. If you haven't read that part, now's a great time, since this part builds on it.

The brain is probably more complicated than our current models permit.

[…]

When you hear about alien lifeforms, one of the most common phrases is "silicon-based life." The idea crops up often in science fiction—but what does it mean? Would it really look like burnt pizza? Is it even possible? What other forms of life are there?

Previously, we looked at the basic concepts of evolution from the perspective of research biology. If you haven't already read Part I, you might wish to do so.

Previously, we looked at the basic concepts of evolution from the perspective of research biology. If you haven't already read Part I, you might wish to do so.

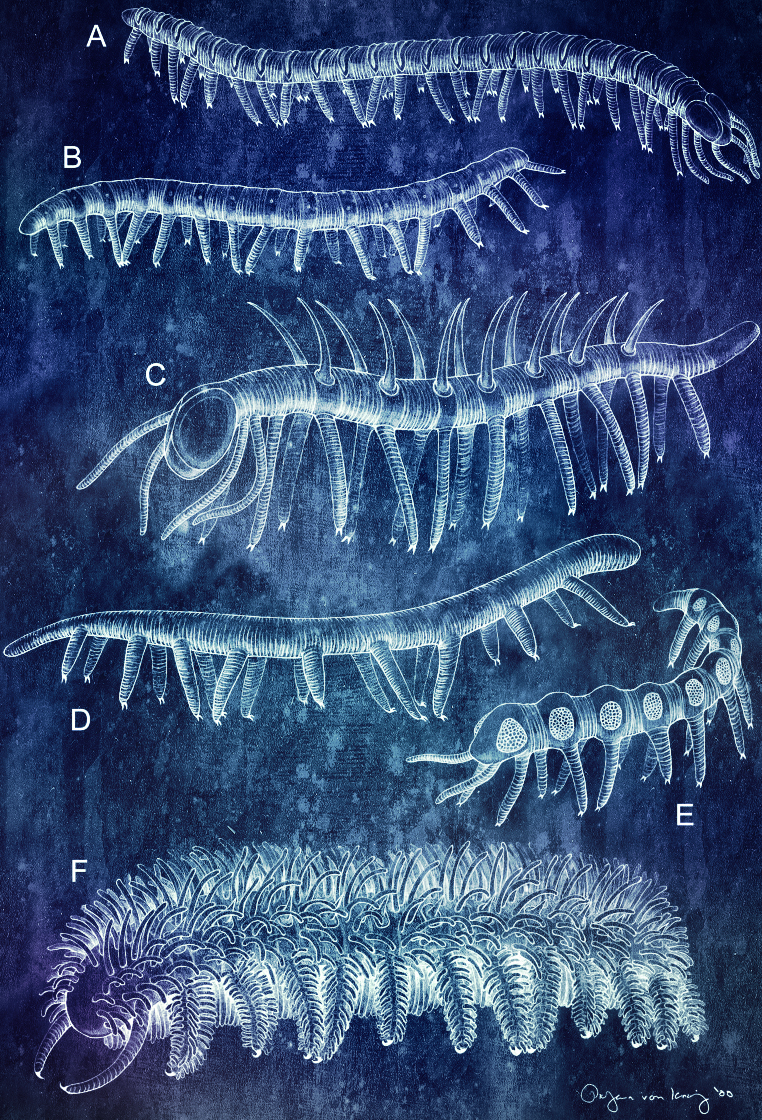

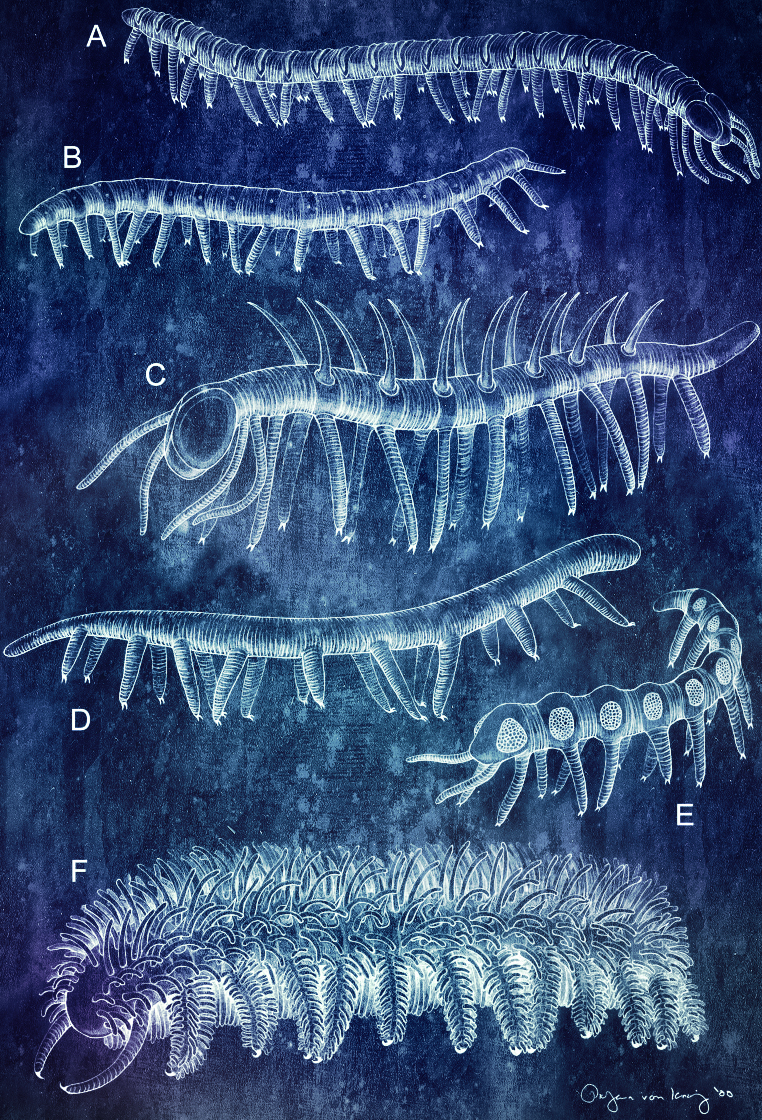

Examples from the phylum Onychophora, one of the most peculiar kinds of worms.

[…]

The tree of life on this planet undergoes extensive and regular pruning. Understanding how this process occurs is essential to creating a constructed world with a plausible biosphere. The art of creating a biosphere, like the art of creating a detailed family languages, is distinguished by the fact that you can do as much or as little as you like, and still captivate a casual reader—but you will still have a rotten taste in your mouth if you skimp on constructing a plausible history. […]

One of the easiest mistakes to make for a fledgling language designer is to make every part of the language elaborate and unique. There are plenty of examples of this throughout the real history of the world—particularly in the form of pictographic writing systems—but there are few, if any, alive today. Why?

BJ945 cuneiform, shot by Charles Tilford. Cc by-nc-sa.

[…]